Fabiana Kent Paiva

doi: 10.18278/aia.4.3.4

Fabiana is an Advocacy and Mobilization Advisor for World Vision Brazil. In this role she works to strengthen the UN Sustainable Development Goals in Brazil. She holds Masters degrees in International Relations and in Art History. Her research interests include visual politics, security, identity and borders.

Fabiana is an Advocacy and Mobilization Advisor for World Vision Brazil. In this role she works to strengthen the UN Sustainable Development Goals in Brazil. She holds Masters degrees in International Relations and in Art History. Her research interests include visual politics, security, identity and borders.

Introduction

In the early 2000’s, after decades of an intricated conflict between Israel and Palestine, the Jewish State was hit by numerous suicide bombings, which triggered the beginning of the construction of the West Bank Wall by the Israeli government in 2003. The separation wall, which led to a radical change in the landscape of the region and remains controversial. It figures prominently in the discussions about the animosity between the two countries and human rights practices. Further, it has been hard to define a resolution to the issue, despite international pressure and mediation. There have been several approaches from different actors that have tried to draw the world’s attention to the Palestinian struggle, from suicide bomb attacks to artistic production. This essay briefly exposes the conflict, the wall’s building, and provides a discussion about the artistic production that has been developed as murals, street art, and political graffiti in the West Bank Wall. Through the analysis of literature and examples of national and international artistic interventions, this essay proposes that these forms of art, produced by local and international actors, can be seen as forms to strengthen the Palestinian identity, draw attention to their struggle and reclaim their right to the land.

The War and the Wall

The conflict between Israel and Palestine has been one of the most pressing matters in international politics since 1947. In that year, following the holocaust and the displacement of the surviving Jewish population in Europe, the United Nations designated part of the territory of Palestine, under British control since the 1910s, to form Israel. The creation of Israel also catered to the Zionist movement’s hopes for a promised land, but did not please the Arabs living in the region: many Palestinian families had been living there for decades and were suddenly ruled by a Jewish government. The following historical context provides the backdrop for this essay.

Since 1947, many armed conflicts have taken place in the limits between the two states. The well-funded and ideal-oriented Israeli State has been able since then to push back Palestinian efforts, supported by the other Arab States, to regain territory. In consequence, Israel has taken over more and more territories, confining Palestinians to small patches of land that are heavily surveilled and controlled by the Jewish State. Palestine resists Israeli settlements and attacks that have been identified in many Western countries as terrorism.

The increase in the use of suicide bombings in the first decade of this century by Palestinian resistance movements such as Hamas and Fatah caused Ariel Sharon, who was by then Prime Minister of Israel (Sharon held office from 2001 to 2006), to establish a policy of War on Terror. There was public pressure on the Prime Minister to take action against the suicide bombings, and his response to this claim was the construction of a wall that would isolate the West Bank region, from where came most of the attacks, from the Israeli territory. The construction began in 2003, following plans to make a wall 26 feet tall and over 440 miles long.

The West Bank Wall was put up as much as 14 miles east of the Green Line, the border set between the two territories in 1949, demanding expropriation of Palestinian land for its construction. Hundreds of families were separated from their houses, farms and water sources, and isolated from the outer world. The circulation of people in and out of the area is controlled by about 540 Israeli checkpoints that oversee the flow of cars and pedestrians. Inside of the wall, the situation is calamitous: Israel has deprived Palestinians from basic freedoms and material supplies, which often come from humanitarian aid organizations, but are frequently blocked by the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) that state that certain materials may be used to make bombs[1].

The international community criticized the construction of the wall. The United Nations General Assembly stated that the construction of the wall and the Jewish settlements inside Palestinian territory breached international law. The Israeli government has ignored the resolutions by the UN that determine that the right for self-determination has been denied to Palestinians since the wall was erected. Israel also disregards several other humanitarian laws, such as the use of excessive force against civilians, the illegal occupation of land and refusal to let humanitarian aid reach the Palestinian people.

Art and Protest

The disrespect to basic human rights by the Israeli government has led to many demonstrations of solidarity towards the Palestinian. Many initiatives to draw international attention to the situation have been developed, such as the BDS movement, which stands for boycott, divestment, and sanctions, that proposes a ban on Israeli products, and urges for more international action against the State. Apart from that, international artists and other support organizations that are pro-Palestine have declined or cancelled visits and shows in Israel. These include Roger Waters, Radiohead, and Lauryn Hill. The artistic field, as it has always been, is a resistance front for conflicts such as the one happening between Israel and Palestine.

The West Bank Wall has also been the stage for different artistic expressions regarding the situation in the region. Different kinds of urban art can be seen in the entire wall’s length. That usage of art is not a surprise since it has been used for millennia as a form of human expression and a way to depict important historical moments and movements. The conflict between the two nations has been the subject of urban art even before the construction of the wall. In the 1980s, during the First Intifada[2], urban art was already used by Palestinians as a means of communication within different communities, and also to keep alive the image of national symbols that were banned by the Israeli authority at the time, such as the Palestinian flag. These drawings, phrases, and symbols were how the locals could communicate and express their resistance, in an extremely surveilled environment, where Israel was constantly erasing these expressions from the Palestinian walls.

Urban art was also important to keep alive the Palestinian nationalism and to maintain the hope of victory among the locals. In “The writing on the walls: the graffiti of the Intifada” (2012), Julie Peteet narrates the story of a young woman in Ramallah who, when asked if she was used to reading the graffiti, answered that to her it was a relief to see them because then she knew that the Palestinian resistance was still alive. The idea of people fighting for their freedom and land was reassuring.

The same modus operandi has been used after the construction of the West Bank Wall. Different resistance groups, as well as other actors, have drawn attention to the meanings and the size of the wall that signifies its oppressive aspects. The landscape has changed for Palestinians since the beginning of the millennium, and to use this symbol of oppression to express identity, resistance, love, and the will for freedom has been a beautiful way to give it a different meaning, as the following image depicts.

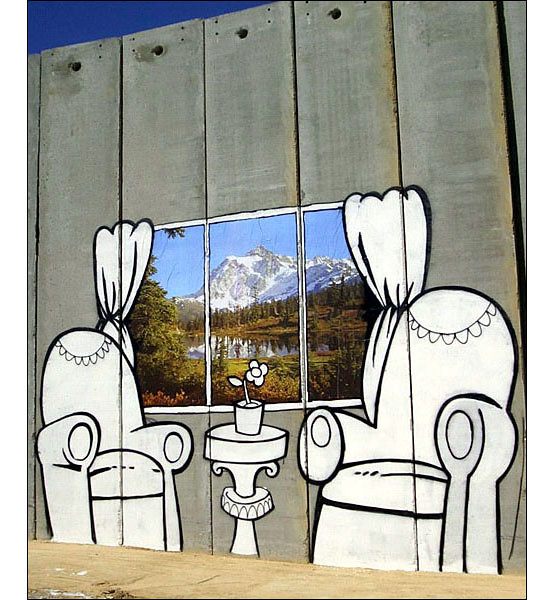

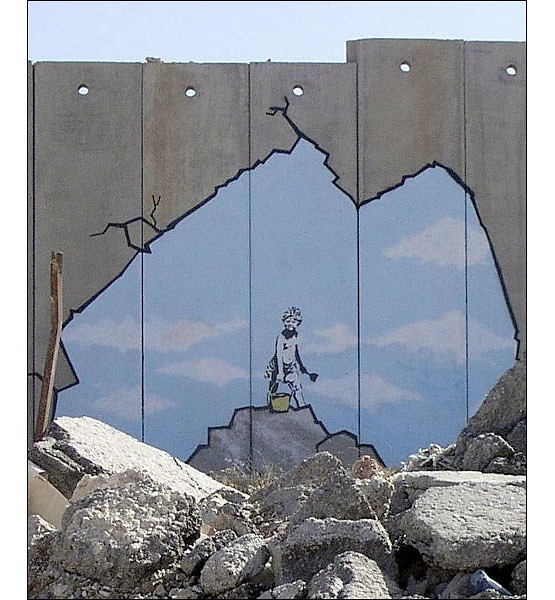

Since the First Intifada, however, there have been changes in the urban art in Palestine. In the 1980s, the most common expressions were drawings and words that did not intend to be visually pleasant, only to send specific messages. The urban art present today in the West Bank Wall still has much of political graffiti, but also a lot of street art and murals[3], and that change has to do with the presence of a very famous urban artist: Banksy. In 2005, the artist visited places such as Bethlehem and Abu Dis, cities that have been impacted by the construction of the wall, and created nine big murals, all of which depicted the need to go through or destroy the barrier[4]. Examples of his work on the Wall can be found below.

Banksy’s murals were spread all over the wall, drawing the attention of politicians, citizens, and artists to the Palestinian struggle. From that intervention, Banksy influenced the way locals related to their urban art, and also the way that the world dealt with the wall. Since then, the local artists refined their artistic interventions, and started to produce murals in which tributes were paid to heroes of the Palestinian cause, such as Leila Khaled—leader of Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP)—that can be seen in a mural in Bethlehem, as you can see in the picture below. The local political graffiti can also be found in the inner parts of the wall, and can be used to spread messages, but also as a way to define the special organization of power in the region. Different resistance groups, such as Hamas, Fatah, and PFLP dispute territories, and use urban art to mark whose influence that neighborhood is under.

Local urban artists also continue using this artistic expression to strengthen the Palestinian identity, with the depiction of national symbols that speak directly to the local population about their history. These symbols are present in murals and also in street art, and vary from one place to the other, containing images that have deep emotional significance to different communities. National symbols that are present in many locations generally refer to Palestine before Israel was created and express the Palestinian hopes and memories: the Palestinian map before 1947, the national flag, the clenched fist, the key, the olive tree, among others.

Unlike the map and flag that are common symbols of nationalism and can be easily understood by outsiders, as well as the fist, known to symbolize struggle and resistance, other symbols require a certain level of knowledge about the Palestinian history and culture to be grasped. The ‘key’ is one of these symbols: many Palestinians still have the keys to properties that were taken from their families by Israel throughout the last seven decades, and this image conveys their will and hope to return to these lands and properties. The olive tree is also a very important symbol that represents the Palestinian steadfastness. The tree, such as the local population, is resistant to harsh conditions and is known to grow back when cut.

International actors also play an important role in the development of urban art in the West Bank Wall. Banksy visited Palestine at least three other times after 2005 and continued to paint murals and street art in different cities and locations. The artist was also responsible for calling out the attention of other artists, stating that Palestine was both an open-air prison and a destination for graffiti artists. Since then, many professional urban artists have gone to the region to paint, but there has also been an interesting movement from tourists all over the world that go to the wall to express their support to Palestine, ask for peace and for the destruction of the wall. There are messages written in many languages, criticizing the lack of action by the UN on the matter, but also encouraging Palestinians to resist.

Facing the enormous amount of urban art being produced on the wall, Israel stopped erasing what was painted on the barrier, which made it one of the biggest canvases in the world, much like what happened to the Berlin wall, visited daily by hundreds of tourists that want to see the art portrayed there. The presence of urban art on the wall combined with the modern technologies that allow tourists to photograph and share these images on social media, has had a political impact on the existence of the wall. These images spread information about the existence of a wall that disrespects human rights and the situation of the Palestinian population, helping the cause by provoking discussions and mobilizing protests.

However, there is another side to the so-called “beautification” of the wall. Many Palestinians think that the presence of urban art makes the wall more palatable since it is filled with beautiful art. They argue that a grey plain wall would be more shocking and therefore would show itself as it is: an instrument of violence and deprivation. There had also been discussions about touristic agencies that specialized in tours that show the urban art on the wall or artists using the wall to publicize their work, and as such are profiting from the Palestinian struggle and not necessarily contributing to their resistance. This discussion is addressed in the following video:

Final Thoughts

The discussion about the beautification and consequent normalization of the wall through the use of urban art can be proficuous, but one can argue that history provides us with a different point of view. The Berlin wall, the most famous physical border in human history, has been a known canvas for urban art since before its fall in 1989, and continues to draw tourists to the art produced in its remains. Art has been important to stress the necessity to talk about the horror such physical border brought to Berlin, and the same goes to the horrors still imposed by the West Bank Wall and in another highly controversial construction: the United States of America and Mexico border wall.

In July 2019, the architect and university professor Ronald Rael planned and executed a beautiful artistic intervention on the border that separates El Paso (USA) and Ciudad Juaréz (Mexico). The intervention is the subject of the video below. Rael built seesaws that connected kids and adults on each side of the wall to represent the consequences that actions taken in one side of the border have on the other side. The seesaws brought to the wall a playful atmosphere that clashed so violently with the purpose of the construction that the intervention became news worldwide, contributing to the discussion about the legality and morality of the wall.

The artistic interventions on the West Bank Wall can be a powerful ally to the Palestinian people since they are powerful tools that show the world a humanistic side of their struggle under Israeli occupation: their confinement inside the eight meter tall barrier. The images of these artistic interventions can be easily accessed on the internet in different blogs, newspapers, social media, and have also helped the local economy by bringing tourists to the region. Art has always been used as a form of resistance against dictatorships, violent regimes, wars, walls, and human rights violations, and so it is on the West Bank Wall.

Footnotes

[1] For more information on the construction of the West Bank Wall, check “The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World—Updated and Expanded”, by Avi Shlaim (2014).

[2] The First Intifada was a Palestinian uprising against Israel that began in 1987 and lasted for 6 years. It was triggered by the death of four residents of a Palestinian refugee camp that was run over by an Israeli truck driver. Many protests broke out in several territories, and violence erupted. Thousands were killed, drawing international attention to the conflict between Israel and Palestine (Shlaim 2014).

[3] In this essay, the classification of the different styles of urban art follow the definitions provided by Claudia Romano, in “Murals, Street Art and Graffiti: How Philadelphia Artist Maneuver the Politics of Public Space (2017).

[4] For Banksy’s works in the wall and around the world, check out Banksy’s “Wall and Piece” (2005).

References

Banksy. (2005) Wall and Piece. UK: Random House.

Peteet, Julie. (2012) The Writings on the Walls: The Graffiti of the Intifada. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/656446> (Accessed 10 September 2019).

Romano, Claudia. (2007) Murals, Street Art, and Graffiti: How Philadelphia Artist Maneuver the Politics of Public Space. 2017. <https://scholarship.tricolib.brynmawr.edu/handle/10066/19180> (Accessed 10 September 2019).

Shlaim, Avi. (2014) The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World—Updated and Expanded. New York: W.W. Norton & Company.